I have been turning this question over in my mind since I read part of a manuscript submitted to BDP that had an interesting technical plot, but flawed characters.

I don’t mean “flawed” in the dramatic sense of a having a tragic, fatal flaw. I mean flawed in the sense of not being real enough, not coming alive on the page.

Characters, if the reader is to accept them as “real”, should be organic, coherent, and individual.

Coherent means behaving in a way consistent with their backstory and personality. If a character does not behave consistently, then we, the readers, might suspect that something is being hidden. That is the character has a secret or a psychological disorder. But if this turns out not to be the case, then the result is akin to reading prose with a series of stupid, grammatical or spelling errors that make the reader lose confidence in the writer and, ultimately, not care about the characters.

Organic is another way of expressing coherence. What a character does should flow from everything else that the reader knows about the character. When the character does something surprising, the reader should feel as if she understands why. If not, the reader carries some confusion, which the writer can use to build tension or hint that the character has a terrible secret – as long as the tension is eventually resolved and the inconsistency is explained.

Individual means have a distinct personality: mannerisms, ways of speaking, etc. I recently read “A People’s History of the Vampire Uprising” by Raymond Villareal. The plot (about vampirism as an eerie viral infection) was well thought out, but many of the characters sounded the same. (Much of the narrative was first-person accounts.) I didn’t end up caring about the characters or believing in them, because they weren’t distinct enough. Their diction (in the first-person accounts) was too similar for me to get invested in the book. Reviews of this book were generally positive, maybe because the technical aspects of the book were pretty cool. However, I also want characters that I can believe in.

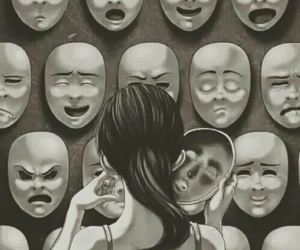

What’s the solution to the problems I’ve raised? Empathy, for starters. You, the writer, should feel empathy for the characters, even the unlovable ones.

Of course, empathy doesn’t solve all the niggles that I described at the outset. Once a character becomes real, you have to let that character do what she wants. You set up a situation in fiction, and if the characters are sufficiently real, then there will be limited options for that particular character in that particular situation. Creating a rich history for the character and listening – listening inside your head – to how the character speaks are also important. So, when a character wants to do something… let him.

Comments are closed